Invasion of the Killer Cicadas

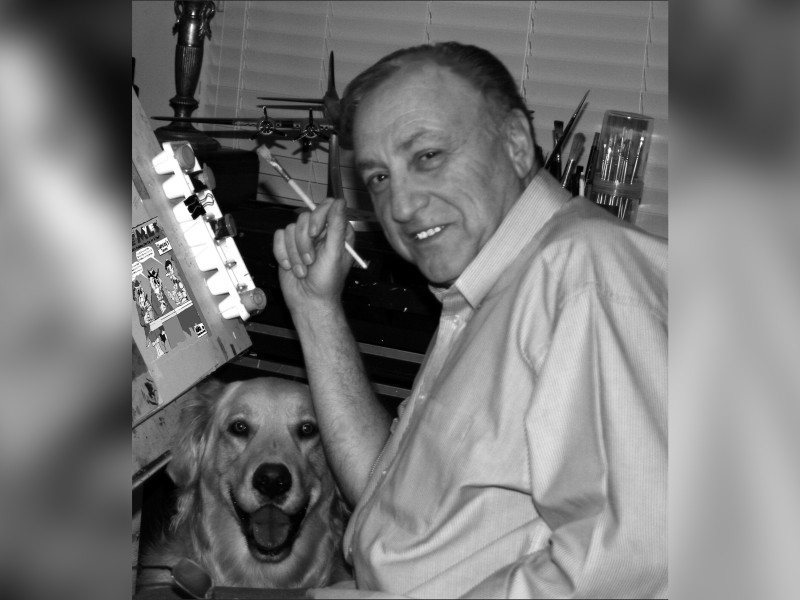

A 13-year cycle cicada has big red eyes, but is harmless as it rests on the author’s finger. (Courtesy: John Trussell)

As I recently got out of my truck in Oaky Woods, I heard a very loud roar that seemed to be coming from all the woods around me. The ominous and foreboding sound was unsettling like the woods were being invaded by some type of alien life force. In 2024, we have experienced a leap year, a solar eclipse and now these strange noises. What’s going on?

If you use a little imagination, thoughts of the HG Wells classic story, “War of the Worlds,” come to mind, where alien pods suddenly spring to life after being buried in the ground for thousands of years. Of course, these alien beings wreak death and destruction on humanity. If you have not seen the movie “War of the Worlds” with Tom Cruise, I suggest you check out this great flick.

Of course, I knew the loud roar was nothing to fear. It was the sound of millions of 13-year-cycle cicadas making a dull drumming sound, but not to attract humans to devour their flesh! Their purpose was a lot more common and harmless. They were looking for love and attempting to attract a mate!

Though there are several different species of periodical cicadas, they have similar life cycles. Immature cicadas hatch from eggs laid on tree branches and then fall to the ground. Young cicadas are white and ant-like in appearance. These juveniles burrow 6 to 18 inches underground and feed on sap from plant roots.

They will spend the next thirteen or seventeen years underground, feeding and developing until they have nearly reached maturity. Mature juveniles sometimes create “cicada huts” when emerging from moist soils, which are tubes made from mud that rise three to five inches above the ground. Cicadas use these structures to emerge from the ground. After emerging through the cicada hut, they climb onto nearby vegetation or other vertical surfaces at night. They then shed their outer skin in a process called molting, becoming fully mature adults.

These cicada emergences are synchronized, meaning that many individuals go through this process at the same time. Up to a million individuals per acre can emerge within seven to ten days of one another. Five to eighteen days after emergence, adult males begin making their characteristic loud mating calls using organs called tymbals to attract female cicadas. These mating calls can exceed 90 decibels, making them about as loud as a lawn mower. Once a female has located a suitable partner, the pair mates. Males often mate with multiple females. After mating, females create 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 inch diameter slits in the bark of small twigs and lay eggs in these crevices. Eggs will hatch in about six to ten weeks, beginning the cycle anew as the young cicada burrows into the ground, where it feeds on tree roots for 13 or 17 years.

Despite the minor damage they cause to plants, periodical cicada years are quite beneficial to the region’s ecology. Their emergence tunnels in the ground act as natural aerators of the soil. The large number of adult cicadas provides a food bonanza to all sorts of predators, which can have a positive impact on their populations. After cicadas die, their decaying bodies help to enrich the soil with nutrients.

There is no need to despair for those who may be concerned whether these insects pose a risk to their personal health and safety. While male cicadas make noise when handled, they cannot bite or sting, so they pose no risk to humans and animals. Cicadas are a part of the natural world around us, mysterious and wondrous!

Before you go...

Thanks for reading The Houston Home Journal — we hope this article added to your day.

For over 150 years, Houston Home Journal has been the newspaper of record for Perry, Warner Robins and Centerville. We're excited to expand our online news coverage, while maintaining our twice-weekly print newspaper.

If you like what you see, please consider becoming a member of The Houston Home Journal. We're all in this together, working for a better Warner Robins, Perry and Centerville, and we appreciate and need your support.

Please join the readers like you who help make community journalism possible by joining The Houston Home Journal. Thank you.

- Brieanna Smith, Houston Home Journal managing editor