A tale of two counties

The trip from Watkinsville, Ga., to Alamo, Ga., covers a little over 140 miles and, according to Google Maps, should take about two hours and 40 minutes. It’s pretty much a straight shot down U.S. 441. You’ll cross I-20 at Madison, go through Milledgeville and then hit Dublin, where you’ll cross I-16, and then make the final half-hour run to Alamo.

Local legend has it that Alamo and a couple of other area towns were named by a railroad man who had moved to Georgia from Texas and couldn’t spell very well. One county to the east you’ll find Uvalda, Ga., named after Uvalde, Tex., and Alston, Ga., named for the state capital of Texas. Alamo was the only one he got right.

In making that trip, however, you’ll cover a lot more than physical distance. You’ll also go from one of the most prosperous counties in the nation to one of the poorest and most distressed. That’s according to the latest report from the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a Washington, D.C., think tank that periodically puts out a new report evaluating nearly all 3,135 counties in the country.

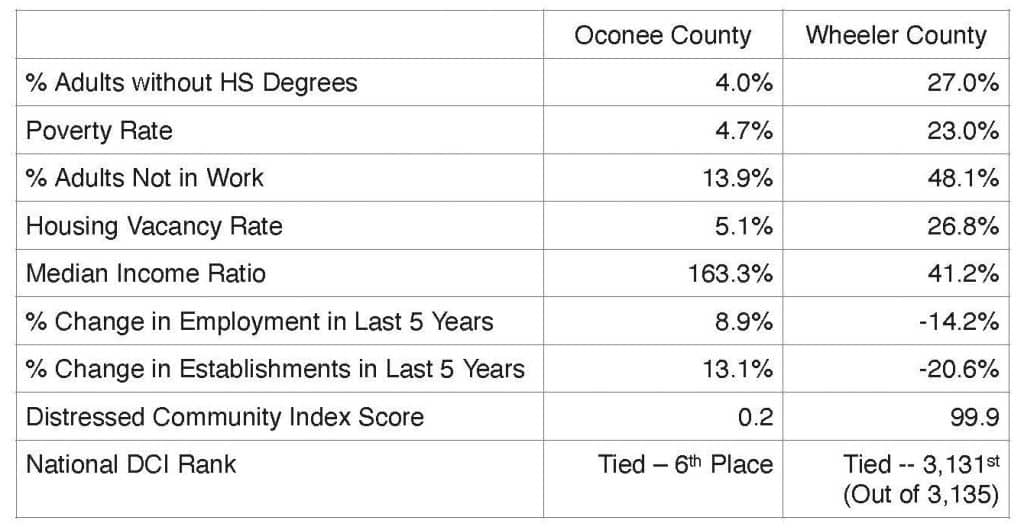

EIG calls this report its Distressed Community Index Report, or DCI, and its 2024 edition came out a few months ago. In this report, EIG grades just about every county in the nation on seven socioeconomic measures drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey project. EIG stirs those numbers together to produce a one-number index for each county. The lower the number, the better; the best possible score is zero and the worst is 100.

Oconee County, of which Watkinsville is the county seat, earned a DCI of 0.2, which was the best in Georgia and tied for 6th nationally. Wheeler County, home to Alamo, got an index of 99.9 and tied with two other counties for 3,131st out of 3,135 counties nationally. EIG’s findings are consistent with my analyses of other data. I found, for instance, that Wheeler County had the lowest per capita income (PCI) in the nation in 2020, and it’s floated around in the bottom three or four since then.

Here’s a look at how Oconee and Wheeler counties scored in each of the categories used by EIG to track community distress levels and calculate their DCIs.

Now, if you’re wondering how and why all those bottom-of-the-barrel Wheeler County numbers are significant – or, for that matter, anybody’s business outside Wheeler County – here’s your answer: All those lousy numbers are really expensive.

Just not for Wheeler County.

Those numbers ripple quickly beyond the Wheeler County line and hit other, more prosperous counties in the pocketbook. A quick analysis of U.S. Census, IRS and Medicaid data for 2020, for example, shows that Wheeler County couldn’t even cover its Medicaid expenses, let alone other social service expenses and public services. Its federal taxes covered just under 60% of its total Medicaid costs.

Oconee County’s total federal tax liability, meanwhile, covered its Medicaid expenses by a multiple of more than 30, and implicit in all these numbers is that Oconee County taxpayers are subsidizing their counterparts in Wheeler County. I offer this data not to embarrass Wheeler County (or to irritate Oconee County) but to impress upon Georgia’s leaders the extent of the divide between the two Georgias – and the costs of that divide.

To some degree, it was ever thus. Nearly every state, county and community has some areas that are better off than others. But the socioeconomic divide in Georgia is growing measurably wider year after year after year. Wheeler Countians are stuck in a part of Georgia that is arguably dying, and their counterparts in Oconee County are stuck with the tab. Georgia’s leaders have a lot of work to do if they’re going to keep the trip from Watkinsville to Alamo from getting any longer or harder, but they owe it to both communities to try.

Charles Hayslett is the author of the long-running troubleingodscountry.com blog. He is also the Scholar in Residence at the Center for Middle Georgia Studies at Middle Georgia State University. The views expressed in his columns are his own and are not necessarily those of the Center or the University.

Before you go...

Thanks for reading The Houston Home Journal — we hope this article added to your day.

For over 150 years, Houston Home Journal has been the newspaper of record for Perry, Warner Robins and Centerville. We're excited to expand our online news coverage, while maintaining our twice-weekly print newspaper.

If you like what you see, please consider becoming a member of The Houston Home Journal. We're all in this together, working for a better Warner Robins, Perry and Centerville, and we appreciate and need your support.

Please join the readers like you who help make community journalism possible by joining The Houston Home Journal. Thank you.

- Brieanna Smith, Houston Home Journal managing editor