Premature Death: the Dow Jones Industrial Average of population health

Years ago, I was talking with a Georgia public health official about how to gauge population health at a local level. “Premature death,” he said. “It’s the Dow Jones Industrial Average of public health. If you want to look at one number and get a feel for the health of a community, look at premature death and whether it’s going up or down.”

He was referring to a public health metric known formally as Years of Potential Life Lost Before Age 75, or YPLL 75. To produce that number, the Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH) keeps track of every death in every county by age and race and stirs them together using a simple equation (see graph above) to generate YPLL 75 Rates for every county in the state.

Backing up my DPH friend’s assessment of the importance of YPPL 75 Rates is the fact that the highly regarded County Health Rankings & Roadmaps (CHRR) project relies heavily on it in generating its “Health Outcomes” rankings for most of the counties in the nation. In fact, 50% of CHRR’s Health Outcomes ratings are determined by a county’s YPLL 75 Rate.

So, against that backdrop, what can YPLL 75 Rates tell us about the population health differences between “Atlanna” (my Trouble in God’s Country 12-county Metro Atlanta region) and “Notlanna” (everything else)? About how the 88-county Great State of South Georgia is faring?

The population health picture is very much in line with the economic and education assessments I sketched out in the last two columns using per capita income, poverty and educational attainment data as key metrics. Basically, the gap between Atlanna and everywhere else has been widening steadily since DPH began tracking and reporting YPLL 75 data in 1994.

Here’s how DPH calculates YPLL 75 Rates. DPH keeps track of every death in the state by county of residence, age and race. People who die under the age of 75 contribute those years to the county’s bucket of years of potential life lost. At the end of each year, DPH totals up all the years of potential life lost for each county, divides that number by the county’s population of people under the age of 75, and then multiplies that number times 100,000. That gives you a rate for each county per 100,000 people.

Forsyth County had the state’s best YPLL 75 Rate in 2022. Its years of potential life lost under the age of 75 totaled 10,852.5 and its YPLL 75 population was 252,467 people. Do the math on that and you get a YPLL 75 Rate of 4,298.6, which would put it in the top 20 counties in the country. At the bottom of the Georgia pile is Baker County in southwest Georgia. It suffered the loss of 509.5 years of potential life lost before age 75 and had a YPLL 75 population of 2,502 people. Run those numbers and you get a YPLL 75 Rate of 20,363.7, which would be in the bottom 20.

The line graph charts the collective YPLL 75 Rate performance for my 12-county Metro Atlanta region and the other 147 counties from 1994 through 2022, and there are several takeaways. The most obvious has to do with the big jump both Atlanna and Notlanna took when Covid-19 hit in 2020 and 2021. Notlanna’s YPLL 75 Rate jumped 39.1% between 2019 and the peak in 2022 while Atlanna’s rose only 30%. (There is one important difference between the Dow Jones Industrial Average and YPLL 75 Rates: With YPLL 75 Rates, the lower the number, the better.)

The more important takeaway, however, has to do with the degree to which the Atlanna and Notlanna lines have diverged over time. In 1994, the premature death gap between Atlanna and Notlanna was 15.8%. That spread hit an all-time high of 44.9% in 2021 and closed back up to 38% in ’22, basically returning to pre-Covid levels.

Those numbers hold obvious implications for both economic productivity and healthcare costs. The healthier a community is, the more it’ll be able to produce economically and the less it will have to spend on healthcare. The converse is also true. The sicker it is, the less it’ll be able to produce and the more it’ll have to spend on healthcare. I’ll flesh this out in future columns.

For now, though, the overriding lesson from this and my previous columns is this: Hugely disproportionate shares of Georgia’s population – mostly rural and almost entirely outside the Metro Atlanta region – seems stuck at the bottom of the nation’s economic, educational and population health ladders.

The reasons things have reached this point are many and complex, but the fact that they still continue to deteriorate constitutes an enormous public policy failure on the part of Georgia’s state government. That failure threatens the future not just of the currently impacted areas, but the entire state. It’s far from clear that Georgia’s state government has the capacity or, frankly, even the desire to do anything about it.

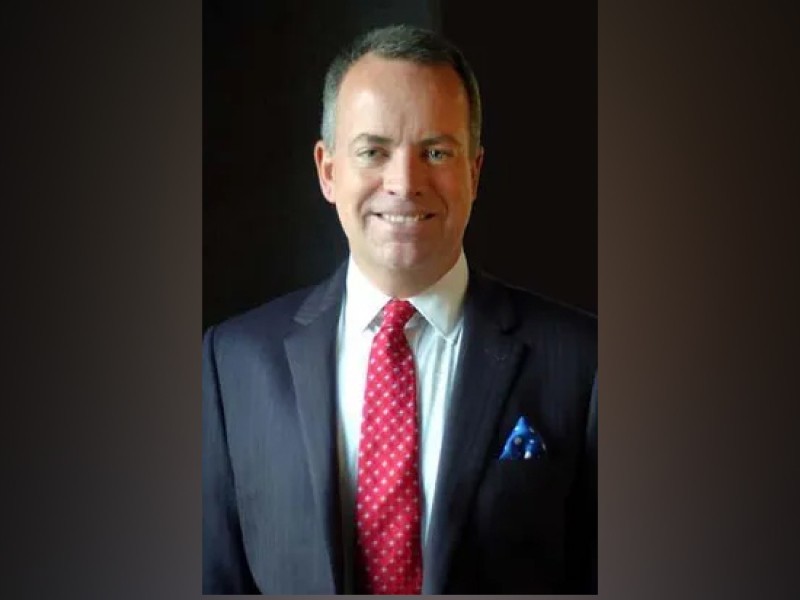

Charles Hayslett is the author of the long-running troubleingodscountry.com blog. He is also the Scholar in Residence at the Center for Middle Georgia Studies at Middle Georgia State University. The views expressed in his columns are his own and are not necessarily those of the Center or the University.

Before you go...

Thanks for reading The Houston Home Journal — we hope this article added to your day.

For over 150 years, Houston Home Journal has been the newspaper of record for Perry, Warner Robins and Centerville. We're excited to expand our online news coverage, while maintaining our twice-weekly print newspaper.

If you like what you see, please consider becoming a member of The Houston Home Journal. We're all in this together, working for a better Warner Robins, Perry and Centerville, and we appreciate and need your support.

Please join the readers like you who help make community journalism possible by joining The Houston Home Journal. Thank you.

- Brieanna Smith, Houston Home Journal managing editor