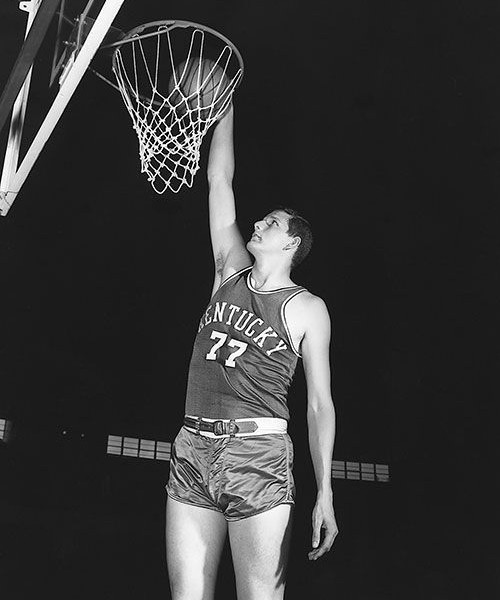

Remembering Warner Robins’ Bill Spivey

Bill Spivey of Warner Robins could have been Wilt Chamberlain or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, instead, he became a forgotten footnote in basketball history; a castaway who chased the game from one minor league outpost to the next, until his body could take no more.

Adolph Rupp, the Baron of the Bluegrass, once said of Spivey: “If he’d have gone on to the professional game, he’d have been the greatest center that ever lived.”

Seven decades later, Spivey remains a compelling “what if” in basketball lore.

Legend has it, during an exhibition game in Milford, Connecticut, circa 1960, an aging Spivey, battled it out with Chamberlain, fresh off his rookie year in the NBA.

“On my team’s first trip down the floor, I got the ball, faked a hook, had Wilt leap to stop it, and then I eased past leaving Wilt, and then I dumped the basket,” Spivey once recollected of the matchup. “Next trip down, I used the same hook, but didn’t fake, and the ball went in over Wilt. Now he was mad. I was willing to fight it out man to man too.”

According to Spivey, he played the Dipper about even, scoring 30 points and collecting 23 rebounds, to Chamberlain’s 31 and 27.

At Warner Robins High School, Spivey was known for his sharp elbows – “they’d cut you to ribbons,” a teammate once said – and oversized feet.

Feet so big – size 15 – he had to play his sophomore year shoeless. The school simply couldn’t find athletic shoes that fit. Three pairs of layered gym socks was all that separated heel from hardwood. Playing home games on a USO dance floor made traction exceptionally difficult.

“I couldn’t stop when I’d run,” he remembered years later.

Even getting socks was a struggle. Spivey would dip his socks in water and then stuff his oversized feet in them, while pulling at the band, stretching the material out.

The following season, the school found him a pair of size 12s. Spivey cut open the caps so his toes could breathe.

Even as a podiatrist’s nightmare, Spivey, who graduated in 1948, managed to score 1,800 points in three seasons of varsity basketball.

“Playing ball, I got all this publicity and the girls started to talk to me,” Spivey told a reporter from the Louisville Courier-Journal, in 1973. “I said ‘Hey, this is alright.’”

A self described “ol’ Georgia country boy,” Spivey dreamed of a life away from his parents’ chicken farm, and the nighttime mosquitos that remained fresh in his memory as an old man.

One day, senior year, he hopped a bus from the farm all the way to Lexington, Kentucky, for an open tryout with college basketball powerhouse, the University of Kentucky.

“I didn’t know they gave scholarships for basketball,” he once remembered. “I wanted to go to Kentucky, sit on the bench and be an All-American. I didn’t know what went into it.”

Rupp was immediately enamored with Spivey – getting an extra kick out of him, every time he had to hunch his shoulders down to walk through a doorway.

Built like a knitting needle, at seven-foot, 170 pounds; Rupp’s first edict was putting weight on Spivey’s country bones.

“[Spivey had] calves like sticks and big knobby knees,” then Kentucky assistant coach Harry Lancaster once remembered.

The summer before his freshman year, under Lancaster’s supervision, Spivey filled out – eventually getting up around 220 pounds – on a heavy milkshake and egg diet.

Wiring Rupp, then coaching a clinic in Germany, Lancaster provided updates on the 19-year-old’s caloric intake.

Rupp wrote back: “Hell, I know he can eat, but can he play?”

Under Rupp, Spivey developed into the best center in the country. In two seasons of varsity basketball, with Spivey under the basket, the Wildcats went 57-5. They won the 1951 National Championship and Spivey was an All-American as well as the Helms Foundation Player of the Year.

Of playing for Rupp, Spivey once said: “Rupp was unique – he wanted everybody to hate him – and he succeeded. Some guys quit. Others took it. We wanted to show him we weren’t the dirty names he called us.”

However difficult Rupp could be, life in Lexington was good. A teammate’s father – a tailor – made him custom suits; the university made him a custom eight-foot-seven-inch bed and the athletic department spent $3.50 per pair of custom basketball sneakers.

Everything came apart after his implication in the college basketball gambling scandal of 1951.

Thirty-two players in all were accused across the country of fixing games or shaving points. It was said that Spivey was paid $1,000 per fixed game. An accusation he vociferously denied.

“I was falsely accused,” Spivey maintained for the rest of his life.

Spivey was tried for perjury in New York in 1952, after being the lone player of the 32 to plead not guilty. The trial lasted 13 days and ended in a hung jury – nine to three in support of his innocence.

Despite the outcome, the University of Kentucky rescinded his basketball scholarship and barred him from playing his senior year.

‘The university told me to prove my innocence,’’ Spivey reflected, years later. ‘’I thought it was the other way around in this country. I think they made me a scapegoat. They were paying players to go to school there and they wanted to stop the investigation from going any further.’’

The NBA followed suit, effectively blackballing Spivey for life.

For 16 years, Spivey hung onto the fringes of the game.

He travelled countless miles crammed in the back of a Station Wagon, or occasionally Chrysler limousine as a member of the New York Olympians – night-in-night-out losers to the Harlem Globetrotters.

Spivey played in the substandard, withered gyms of the Eastern Basketball League alongside fellow basketball undesirables Sherman White and Ed Roman. He played in places like Scranton and Wilkes Barre and in the American Basketball League with the Los Angeles Jets and Hawaii Chiefs. It’s even said that he once scored 100 points in a game.

The Cincinnati Royals attempted to pair Spivey with Oscar Robertson in 1960, offering him a $20,000 contract. NBA commissioner Maurice Podoloff blocked the deal and threatened league wide boycott of the team if they played Spivey.

Spivey sued the NBA for $820,000, eventually settling out of court for only $10,000.

He hobbled away from the game in 1968.

Spivey dabbled in local politics in Kentucky and sold insurance, but he could never really leave the past behind.

“He never got over it,” his ex-wife Audra said in 1995. “Bill could not let that go. He was just devastated.”

At the end of his life, he battled the bottle and became a recluse in Costa Rica. In 1995 he was found dead in his apartment in Quepos.

He was 66 years old.

‘’I think I would have had an era all my own in the NBA,’’ Spivey lamented, years after scoring his final basket. ‘’George Mikan was near the end of his career and Wilt Chamberlain hadn’t started. I was the biggest and the best in the country. I think I would have dominated the game like those two did.’’

HHJ News

Before you go...

Thanks for reading The Houston Home Journal — we hope this article added to your day.

For over 150 years, Houston Home Journal has been the newspaper of record for Perry, Warner Robins and Centerville. We're excited to expand our online news coverage, while maintaining our twice-weekly print newspaper.

If you like what you see, please consider becoming a member of The Houston Home Journal. We're all in this together, working for a better Warner Robins, Perry and Centerville, and we appreciate and need your support.

Please join the readers like you who help make community journalism possible by joining The Houston Home Journal. Thank you.

- Brieanna Smith, Houston Home Journal managing editor